Documenting Extensions#

This guide is for developers who write API documentation. To build the documentation, run:

repo.{sh|bat} docs

Add the -o flag to automatically open the resulting docs in the browser. If multiple projects of documentation are generated, each one will be opened.

Add the --project flag to specify a project to only generate those docs. Documentation generation can be long for some modules, so this may be important to reduce iteration time when testing your docs. e.g:

repo.bat docs --project kit-sdk / repo.bat docs --project omni.ui

Add the -v / -vv flags to repo docs invocations for additional debug information, particularly for low-level Sphinx events.

Note

You must have successfully completed a debug build of the repo before you can build the docs for Python.

This is due to the documentation being extracted from the .pyd and .py files in the _build folder.

Run build --debug-only from the root of the repo if you haven’t done this already.

As a result of running repo docs in the repo, and you will find the project-specific output under _build/docs/{project}/latest.

The generated index.html is what the -o flag will launch in the browser if specified.

Warning

sphinx warnings will result in a non-zero exit code for repo docs, therefore will fail a CI build. This means that it is important to maintain docstrings with the correct syntax (as described below) over the lifetime of a project.

Documenting Python API#

The best way to document our Python API is to do so directly in the code. That way it’s always extracted from a location where it’s closest to the actual code and most likely to be correct. We have two scenarios to consider:

Python code

C++ code that is exposed to Python

For both of these cases we need to write our documentation in the Python Docstring format (see PEP 257 for background). In a perfect world we would be able to use exactly the same approach, regardless of whether the Python API was written in Python or coming from C++ code that is exposing Python bindings via pybind11. Our world is unfortunately not perfect here but it’s quite close; most of the approach is the same - we will highlight when a different approach is required for the two cases of Python code and C++ code exposed to Python.

Instead of using the older and more cumbersome restructuredText Docstring specification, we have adopted the more streamlined Google Python Style Docstring format. This is how you would document an API function in Python:

from typing import Optional

def answer_question(question: str) -> Optional[str]:

"""This function can answer some questions.

It currently only answers a limited set of questions so don't expect it to know everything.

Args:

question: The question passed to the function, trailing question mark is not necessary and

casing is not important.

Returns:

The answer to the question or ``None`` if it doesn't know the answer.

"""

if question.lower().startswith("what is the answer to life, universe, and everything"):

return str(42)

else:

return None

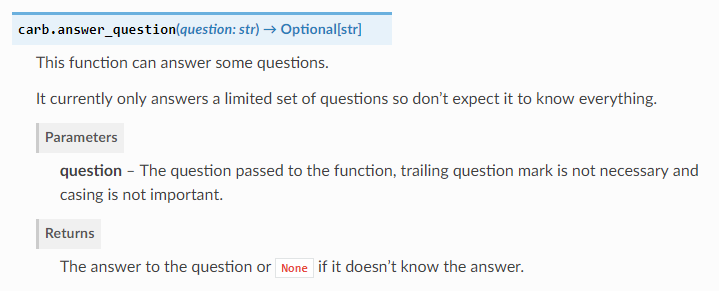

After running the documentation generation system we will get this as the output (assuming the above was in a module named carb):

There are a few things you will notice:

We use the Python type hints (introduced in Python 3.5) in the function signature so we don’t need to write any of that information in the docstring. An additional benefit of this approach is that many Python IDEs can utilize this information and perform type checking when programming against the API. Notice that we always do

from typing import ...so that we never have to prefix with thetypingnamespace when referring toList,Union,Dict, and friends. This is the common approach in the Python community.The high-level structure is essentially in four parts:

A one-liner describing the function (without details or corner cases), referred to by Sphinx as the “brief summary”.

A paragraph that gives more detail on the function behavior (if necessary).

An

Args:section (if the function takes arguments, note thatselfis not considered an argument).A

Returns:section (if the function does return something other thanNone).

Before we discuss the other bits to document (modules and module attributes), let’s examine how we would document the very same function if it was written in C++ and exposed to Python using pybind11.

m.def("answer_question", &answerQuestion, py::arg("question"), R"(

This function can answer some questions.

It currently only answers a limited set of questions so don't expect it to know everything.

Args:

question: The question passed to the function, trailing question mark is not necessary and

casing is not important.

Returns:

The answer to the question or empty string if it doesn't know the answer.)");

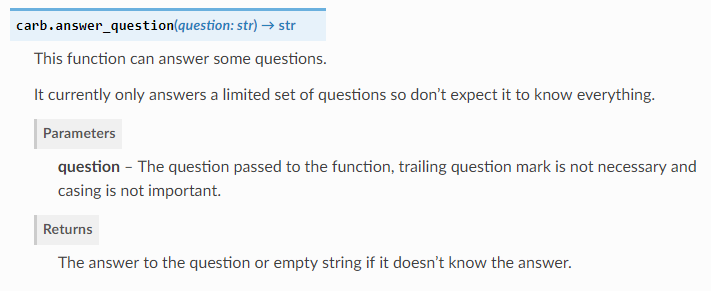

The outcome is identical to what we saw from the Python source code, except that we cannot return optionally a string in C++. The same docstring syntax rules must be obeyed because they will be propagated through the bindings.

We want to draw your attention to the following:

pybind11 generates the type information for you, based on the C++ types. The

py::argobject must be used to get properly named arguments into the function signature (see pybind11 documentation) - otherwise you just get arg0 and so forth in the documentation.Indentation and whitespace are key when writing docstrings. The documentation system is clever enough to remove uniform indentation. That is, as long as all the lines have the same amount of padding, that padding will be ignored and not passed onto the RestructuredText processor. Fortunately clang-format leaves this funky formatting alone - respecting the raw string qualifier. Sphinx warnings caused by non-uniform whitespace can be opaque (such as referring to nested blocks being ended without newlines, etc)

Let’s now turn our attention to how we document modules and their attributes. We should of course only document modules that are part of our API (not internal helper modules) and only public attributes. Below is a detailed example:

"""Example of Google style docstrings for module.

This module demonstrates documentation as specified by the `Google Python

Style Guide`_. Docstrings may extend over multiple lines. Sections are created

with a section header and a colon followed by a block of indented text.

Example:

Examples can be given using either the ``Example`` or ``Examples``

sections. Sections support any reStructuredText formatting, including

literal blocks::

$ python example.py

Section breaks are created by resuming unindented text. Section breaks

are also implicitly created anytime a new section starts.

Attributes:

module_level_variable1 (int): Module level variables may be documented in

either the ``Attributes`` section of the module docstring, or in an

inline docstring immediately following the variable.

Either form is acceptable, but the two should not be mixed. Choose

one convention to document module level variables and be consistent

with it.

module_level_variable2 (Optional[str]): Use objects from typing,

such as Optional, to annotate the type properly.

module_level_variable4 (Optional[File]): We can resolve type references

to other objects that are built as part of the documentation. This will link

to `carb.filesystem.File`.

Todo:

* For module TODOs if you want them

* These can be useful if you want to communicate any shortcomings in the module we plan to address

.. _Google Python Style Guide:

http://google.github.io/styleguide/pyguide.html

"""

module_level_variable1 = 12345

module_level_variable3 = 98765

"""int: Module level variable documented inline. The type hint should be specified on the first line, separated by a

colon from the text. This approach may be preferable since it keeps the documentation closer to the code and the default

assignment is shown. A downside is that the variable will get alphabetically sorted among functions in the module

so won't have the same cohesion as the approach above."""

module_level_variable2 = None

module_level_variable4 = None

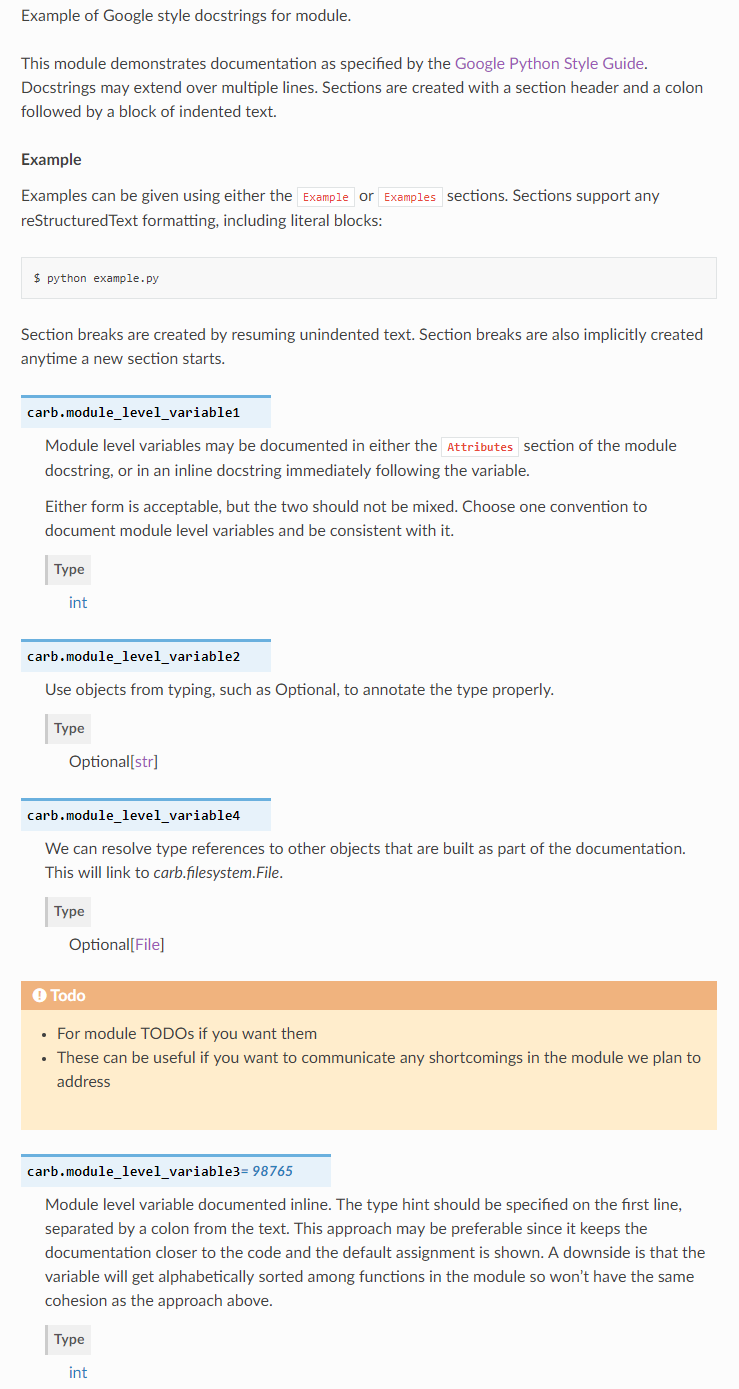

This is what the documentation would look like:

As we have mentioned we should not mix the Attributes: style of documentation with inline documentation of attributes.

Notice how module_level_variable3 appears in a separate block from all the other attributes that were documented.

It is even after the TODO section.

Choose one approach for your module and stick to it.

There are valid reasons to pick one style above the other, but don’t cross the streams!

As before, we use type hints from typing but we don’t use the typing syntax to attach them.

We write:

"""...

Attributes:

module_variable (Optional[str]): This is important ...

"""

or

module_variable = None

"""Optional[str]: This is important ..."""

But we don’t write:

from typing import Optional

module_variable: Optional[str] = 12345

"""This is important ..."""

This is because the last form (which was introduced in Python 3.6) is still poorly supported by tools - including our documentation system. It also doesn’t work with Python bindings generated from C++ code using pybind11.

For instructions on how to document classes, exceptions, etc please consult the Sphinx Napoleon Extension Guide.

Adding Extensions to the automatic-introspection documentation system#

It used to be necessary to maintain a ./docs/index.rst to write out automodule/autoclass/etc directives, as well as to include hand-written documentation about your extensions.

In order to facilitate rapid deployment of high-quality documentation out-of-the-box, a new system has been implemented.

Warning

If your extension’s modules cannot be imported at documentation-generation time, they cannot be documented correctly by this system. Check the logs for warnings/errors about any failures to import, and any errors propagated.

In the Kit repo.toml, the [repo_docs.projects."kit-sdk"] section is responsible for targeting the old system, and the [repo_docs.kit] section is responsible for targeting the new.

Opt your extension in to the new system by:

Adding the extension to the list of extensions.

In

./source/extensions/{ext_name}/docs/, Add or write anOverview.mdif none exists. Users will land here first.In

./source/extensions/{ext_name}/config/extension.toml, Add all markdown files - exceptREADME.md- to an entry per the example below.In

./source/extensions/{ext_name}/config/extension.toml, Add any extension dependencies to which your documentation depends on links or Sphinx ref-targets existing. This syntax follows the repo_docs tools intersphinx syntax. The deps are a list of lists, where the inner list contains the name of the target intersphinx project, followed by the path to the folder containing that projectsobjects.invfile. http links to websites that host their objects.inv file online like python will work as well, if discoverable at docs build time. Apart from web paths, this will only work for projects inside of the kit repo for now.

[documentation]

deps = [

["kit-sdk", "_build/docs/kit-sdk/latest"]

]

pages = [

"docs/Overview.md",

"docs/CHANGELOG.md",

]

The first item in the list will be treated as the “main page” for the documentation, and a user will land there first.

Changelogs are automatically bumped to the last entry regardless of their position in the list.

Python API Automatic Introspection#

When building extension docs [repo_docs.kit] will automatically introspect the extension’s python modules (defined in [[python.modules]]) and add them to the “API (python)” section of the documentation.

To do that, it uses these repo_docs settings:

[repo_docs]

python_paths = []

library_paths = []

To set PYTHONPATH and LD_LIBRARY_PATH/PATH accordingly. Then it runs Kit’s python and tries to import the modules. If failed, it will log a detailed error message, but will not fail the docs build. Python API will be incomplete.

The most common reason of failure is that extension run some logic at import time, like carb.setttings.get_settings() to set some global variables. Those plugins are not available at this point and it will crash. It is in general a good idea to avoid any logic at import time and defer it until extension is started.

Alternatively, we set a special envvar OMNI_KIT_REPO_DOCS_BUILD to 1 when building docs. You can use it to skip some logic at import time.

Dealing with Sphinx Warnings#

The introspection system ends up introducing many more objects to Sphinx than previously, and in a much more structured way.

It is therefore extremely common to come across many as-yet-undiscovered Sphinx warnings when migrating to this new system.

Here are some strategies for dealing with them.

MyST-parser warnings#

These are common as we migrate away from the RecommonMark/m2r2 markdown Sphinx extensions, and towards MyST-parser, which is more extensible and stringent.

Common issues include:

Header-level warnings. MyST does not tolerate jumping from h1 directly to h3, without first passing through h2, for example.

Links which fail to match a reference. MyST will flag these to be fixed (Consider it a QC check that your links are not broken).

Code block syntax - If the language of a code-block cannot be automatically determined, a highlighting-failure warning may be emitted. Specify the language directly after the first backticks.

General markdown syntax - Recommonmark/m2r2 were more forgiving of syntax failures. MyST can raise warnings where they would not previously.

Docstring syntax warnings#

The biggest issue with the Sphinx autodoc extension’s module-introspection is that it is difficult to control which members to inspect, and doubly so when recursing or imported-members are being inspected.

Therefore, it is strongly advised that your python modules define __all__, which controls which objects are imported when from module import * syntax is used. It is also advised to do this step from the perspective of python modules acting as bindings for C++ modules.

__all__ is respected by multiple stages of the documentation generation process (introspection, autosummary stub generation, etc).

This has two notable effects:

Items that your module imports will not be considered when determining the items to be documented. This speeds up documentation generation.

Prevents unnecessary or unwanted autosummary stubs from being generated and included in your docs.

Optimizes the import-time of your module when star-imports are used in other modules.

Unclutters imported namespaces for easier debugging.

Reduces “duplicate object” Sphinx warnings, because the number of imported targets with the same name is reduced to one.

Other common sources of docstring syntax warnings:

Indentation / whitespace mismatches in docstrings.

Improper usage or lack-of newlines where required. e.g. for an indented block.

C++ docstring issues#

As a boon to users of the new system, and because default bindings-generated initialization docstrings typically make heavy use of asterisks and backticks, these are automatically escaped at docstring-parse time.

Please note that the pybind11_builtins.pybind11_object object Base is automatically hidden from class pages.